How stories have shaped the world

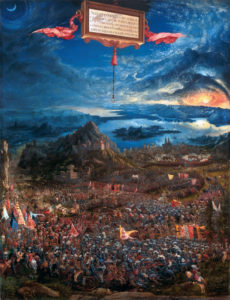

From a young age, Alexander the Great was groomed to be the leader of Macedonia. The small kingdom in northern Greece was perpetually at war with its neighbors, above all Persia, which meant that Alexander had to learn how to lead armies into battle. When his father was assassinated Alexander ascended the throne, he quickly exceeded all expectations. Not only did he secure the safety of his kingdom, but he also defeated the entire Persian Empire, conquering a vast realm that stretched from Egypt to Northern India.

From a young age, Alexander the Great was groomed to be the leader of Macedonia. The small kingdom in northern Greece was perpetually at war with its neighbors, above all Persia, which meant that Alexander had to learn how to lead armies into battle. When his father was assassinated Alexander ascended the throne, he quickly exceeded all expectations. Not only did he secure the safety of his kingdom, but he also defeated the entire Persian Empire, conquering a vast realm that stretched from Egypt to Northern India.

Alexander possessed an additional weapon: Homer’s Iliad. He had learned to read and write by studying this text as a young man, and thanks to his teacher, the philosopher Aristotle, he had done so with unusual intensity. When he embarked on his conquests, Homer’s story of an earlier Greek expedition to Asia Minor served as a blueprint, and he stopped at Troy, even though the city had no military significance, to re-enact scenes from the Iliad. For the entire duration of his conquest, he would sleep on his copy of the Iliad, the one annotated by his teacher Aristotle.

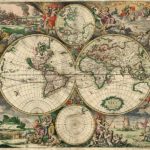

The influence between the Iliad and Alexander went both ways. Having drawn inspiration from the epic, Alexander gave back to Homer by turning Greek into the common language of a large region, thus laying the infrastructure for turning the Iliad into world literature. Alexander’s successors built the great libraries of Alexandria and of Pergamum that would preserve Homer for the future.

Homer’s Iliad was typical of early works such as the Epic of Gilgamesh of Mesopotamia or the Mayan Popol Vuh. This epic literature served as a common reference points for entire cultures, telling their audiences where they came from and who they were.

Homer’s Iliad was typical of early works such as the Epic of Gilgamesh of Mesopotamia or the Mayan Popol Vuh. This epic literature served as a common reference points for entire cultures, telling their audiences where they came from and who they were.

But not all literary traditions begin with epic narratives of kings and conquests. Chinese literature is based on the Book of Songs, a collection of deceptively simple poems that have since accrued a large body of interpretation and commentary. Poetry was not only the province of professional poets. An aspiring bureaucrat of China’s vast government apparatus had to pass through the rigorous imperial examination system, which required a detailed knowledge of poetry, and higher government officials were expected to be able to dash off casual poems on a whim. The Book of Songs enshrined poetry as the most important form of literature across East Asia. (When Japan sought cultural independence from China, it did so by creating its own poetry collection.)

The importance of poetry also shaped one of the first great novels in world literature: the Tale of Genji. Its author, Murasaki Shikibu, had to teach herself Chinese poetry, by spying on her brother’s lessons with a tutor, since women were not expected to know Chinese literature. When she became a Lady-in-Waiting at the secretive court of Japan, she used this knowledge to compose a portrait of life at court, full of detail and psychological insight, producing a masterpiece that grew to over a thousand pages. To give her novel the status of high literature, she included nearly eight hundred poems.

The importance of poetry also shaped one of the first great novels in world literature: the Tale of Genji. Its author, Murasaki Shikibu, had to teach herself Chinese poetry, by spying on her brother’s lessons with a tutor, since women were not expected to know Chinese literature. When she became a Lady-in-Waiting at the secretive court of Japan, she used this knowledge to compose a portrait of life at court, full of detail and psychological insight, producing a masterpiece that grew to over a thousand pages. To give her novel the status of high literature, she included nearly eight hundred poems.

As more and more parts of the world became literate, new technologies, above all paper and print, increased the reach and influence of written stories. Both inventions lowered the cost of literature, which meant that new groups of readers could have access to written stories. And new readers meant new stories started to appear, catering to these readers’ tastes and interests. This development was particularly visible in the Arabic world, which had acquired the secret of making paper from China and turned it into a thriving industry. For the first time, stories that had only been told orally made it into writing and were assembled in story collections such as the One Thousand and One Nights. More varied than the older epic stories or poetry collections, the One Thousand and One Nights provided entertainment and education in equal measure, framed by the unforgettable story of Scheherazade and the king who had sworn to kill any woman after spending only one night with her. Faced with the prospect of certain death, Scheherazade began to tell story after story until the king found himself cured of his murderous oath—making Scheherazade not only his queen but also the hero of storytelling.

Poetry collections, story collections, and epic tales cast a long shadow over subsequent literary history. When the Italian poet Dante Alighieri set out to capture and elaborate the Christian view of Hell, Purgatory, and Heaven, he chose the form of epic poetry, thus competing with classical authors (cleverly, he put Homer in limbo since Homer had the misfortune of living before Christ). Dante wrote this Comedy not in highly regarded Latin, but in the spoken dialect of Tuscany. The decision helped turn that dialect into the legitimate language we now call Italian, a tribute to the importance of literature in shaping language.

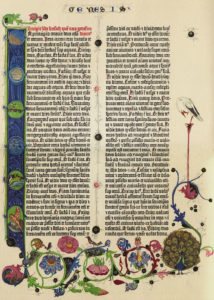

The single greatest change in the fortunes of literature occurred with the invention of print in Northern Europe by Johannes Gutenberg (drawing on Chinese techniques), who ushered in the era of mass production and mass literacy we have today. In terms of literature, that era came to be dominated by the novel, named for its “novelty” despite important predecessors such as Lady Muraski. Novels didn’t have the baggage associated with ancient forms of literature and therefore allowed new types of authors and readers to emerge, especially women, who used the flexible form to grapple with the most pressing questions of modern society. Mary Wollstonecraft’s Frankenstein stands at the beginning of what would come to be known as science fiction, torn between the utopian promise of science and its destructive potential. (The political dystopias of George Orwell’s 1984 and Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale are more recent examples of that tradition.) At the same time, the novel was used by new and emerging countries to assert their independence, as happened during the so-called Latin American boom in the nineteen sixties with Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude, a multi-generational novel hoping to capture an entire culture. Political independence required cultural independence, and novels proved the best way of gaining it.

The single greatest change in the fortunes of literature occurred with the invention of print in Northern Europe by Johannes Gutenberg (drawing on Chinese techniques), who ushered in the era of mass production and mass literacy we have today. In terms of literature, that era came to be dominated by the novel, named for its “novelty” despite important predecessors such as Lady Muraski. Novels didn’t have the baggage associated with ancient forms of literature and therefore allowed new types of authors and readers to emerge, especially women, who used the flexible form to grapple with the most pressing questions of modern society. Mary Wollstonecraft’s Frankenstein stands at the beginning of what would come to be known as science fiction, torn between the utopian promise of science and its destructive potential. (The political dystopias of George Orwell’s 1984 and Margaret Atwood’s Handmaid’s Tale are more recent examples of that tradition.) At the same time, the novel was used by new and emerging countries to assert their independence, as happened during the so-called Latin American boom in the nineteen sixties with Gabriel Garcia Marquez’ One Hundred Years of Solitude, a multi-generational novel hoping to capture an entire culture. Political independence required cultural independence, and novels proved the best way of gaining it.

While these and many other authors profited from the era of mass literacy, the printing press also made it easier to control and censor literature. This became a particular problem for authors living in totalitarian regimes such as Nazi Germany or the Soviet Union, where systems of underground publication developed in order to evade censorship.

Today, we are living through yet another revolution in writing technologies, one at least as important as the invention of paper and print in China or the re-invention of print in Northern Europe. The internet is changing how we read and write, how we multiply literature and who has access to it. We stand at the beginning of a new era of writing and literature—the written world is bound to change yet again.

Martin Puchner

This text originally appeared on the BBC on April 23, 2018

Join over a hundred thousand students, from 160 countries, who have taken this free HarvardX course, which provides and overview of world literature. It includes travel footage, interviews, and discussions. Rated top MOOC in literature: “look no further than Masterpieces of World Literature” (E-Learning Inside).

Enroll here.